They say that your mind can play tricks on you, but this is

ridiculous.

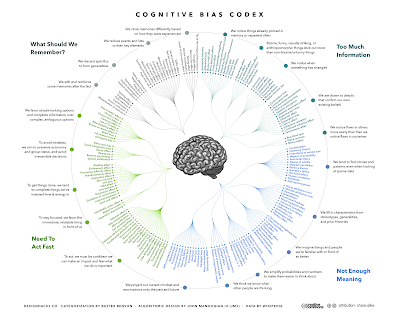

Are you thinking of a cognitive bias, but you can’t recall

its name? Do you ever suspect fallacious thinking, but can’t diagnose its

cause? Sure, we’ve all been there.

But now there’s no need to struggle with

floppy flash cards or your fallible memory. Now there’s the Cognitive Bias Codex! This handy-dandy website and graphic presents, like, ALL of the

cognitive biases, helpfully organized by cause.

Got information overload? Maybe you are “anchoring” or

suffering from “post-purchase rationalization.”

Not exciting enough for you? There’s also the “cheerleader

effect,” the “masked man fallacy,” and even the “endowment effect.” Who said

college was boring?

And these are just some of the more than 150 disquietingly

common mistakes your brain can make!

They’re all here!

Brace for impact folks. Everything you thought you knew is a

lie!

All kidding aside, this is a really useful piece of

scholarship. This website and graphic contain a comprehensive list of cognitive

biases, tricks your mind can play on you which create false impressions and

interpretations that can have serious negative effects. Learn them; know them;

live better.

Click on the image for the full sized version.

Works Cited:

Manoogian, John. “Cognitive Bias Codex 2016.” found at Betterhumans.coach.me.

Sep. 2016. Web. 22 Jan. 2018.

Works Referenced:

Benson, Buster. “the Cognitive Bias Cheat Sheet: Because Thinking

is Hard.” Betterhumans.coach.me. 1

Sep. 2016. Web. 22 Jan. 2016.

Note: the

above websites are associated with the parent website Medium.com. This website apparently

provides no sponsor information about itself, so that information is missing

from the MLA citations.